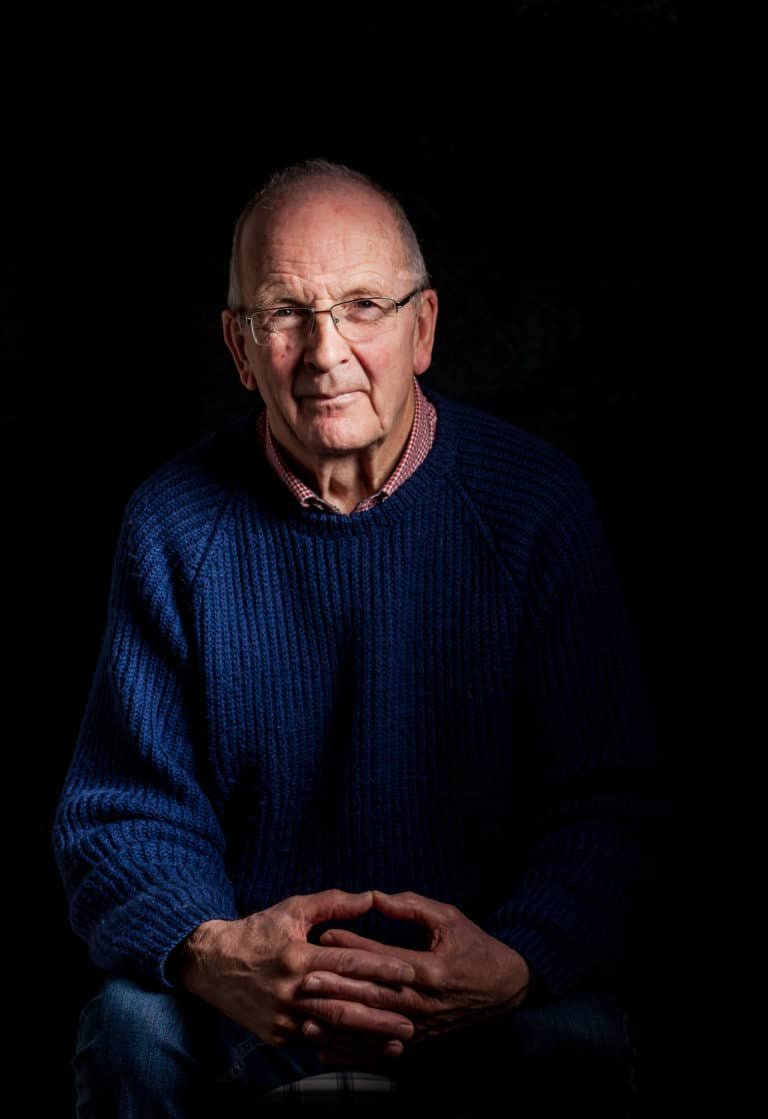

David Cooper on Hay

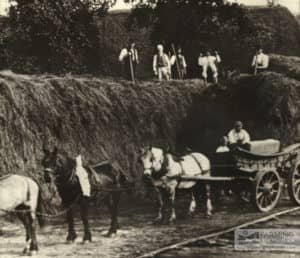

Right, harvest time, the tractor mower would cut the grain. No it wouldn’t, here you are, a binder.

That’s a binder, that’s a horse-drawn binder. This is actually Park Farm before, this is pre-war but by the time I got there the binder was pulled by a tractor.

Same machine. Someone would sit on it and then when the sheave was wrapped up it would just release it and so the tractor driver would be driving across the field and the binder operator would pull the lever and so there would be a row of sheaves, you’ve seen traditional sheaves, and then the next job would be for us to get out there and to stook them up, put them up in stacks, tapered so that the rain ran off them because then if it did rain, it wouldn’t rot the corn.

Then, when that was all done, and there may be several fields, we would then go out with a tractor trailer, horse and cart and pick them up, take them back to the farmyard and then the farmyard would turn into, instead of a big empty space it would be turned into a mini village.

There’d be stacks like that, and that might be one, there would be a round one perhaps for barley, there’d be another one for, a rectangular one for wheat. Wheat was the main crop and so that was then left until… and then they’d be temporarily thatched. The farmer used to put some sort of thatch to keep the rain off them until November.

Sometimes in the winter the thrashing would be done.

Whenever it was fitted in, the thrashing machine would arrive from Barnsley Farm nearby, which is now Goddard’s Brewery and the gentleman there had this big machine. I think it was an Edwardian machine, it was a great big wooden structure and it used to be towed by a tractor.

It had been designed to work with a steam engine, an old traction engine but it used to come with a tractor and then you would need at least five, six people to operate it so that’s when we used to get extra hands in.

After the milking each day, remember the milking had to be done morning and afternoon, I’m probably going ahead of myself actually. After milking had been done, the cows had been sorted out, the milk lorry had arrived, taken the milk away, then we’d get out there and get thrashing.

There was a great big pulley on the side and a belt would drive it from the tractor so that would be rattling away all day and there’d be a man at the top feeding the sheaves in to the drum, the drum was rotating and then it would take the corn through and it would vibrate or hammer it and the grain would come down a chute at the back end of the tractor, the back end of the thrasher and so there would be a man there operating the chute.

It would be a twin chute and there’d be a sack arranged just below the chute so when that sack was filled he’d switch over to the other sack. Sorry, I can’t explain it very well with words but I’m doing it with my hands aren’t I?

So the sacks would then be taken off by a sack truck and put into a grain store where rats and things wouldn’t get it. The other end, the straw was coming out and so there would be someone there and that was tied up with string. The machine would tie it up with string, bind it up and then the straw would then be taken and put into a rick, a stack, something like that and if it was wheat straw it could be used for thatching and every year the farmer used to thatch a different building.

He thatched that. That would last about 20 years, so he told me, and then another year he’d do that one with wheat straw.